The pandemic within the pandemic: Why Black Lives Matter in the Body of Christ (COVID-19 blog no. 11)

It is clear that racism is the pandemic within the pandemic, which was once held at the inarticulate level or the politically unconscious level for the most part, but has now come to the fore. The whole world is waking up to the reality of racism, and there is a renewed desire for anti-racist action.

What COVID-19 can teach us about trans inclusion (COVID-19 blog no. 10)

Re-negotiating space: walking in a time of pandemic (COVID-19 blog no. 9)

You are walking along the footpath and there is someone else walking from the opposite direction. To avoid collision there is a great dance of social awkwardness as you both move in the same direction. After a bout of feigned laughter and mutual hand gesturing the awkwardness eventually ends and you both carry on your merry way. That was pre-COVID-19, of course.

Supporting women involved in prostitution during a pandemic (COVID-19 blog no. 8)

COVID-19 and the survival of the fittest (COVID-19 blog no. 7)

Workers’ rights and the COVID-19 pandemic (COVID-19 blog no. 6)

COVID-19 pandemic and the renewal of political economy (COVID-19 blog no. 5)

COVID and Conflict (COVID-19 blog no. 4)

COVID-19, for all the ‘We’re all in this together’ sentiment, has illuminated the extent to which we are not: disproportionate numbers of BAME people are dying, and we see higher mortality rates in areas of densely-packed housing and in areas of long term, multi-generational deprivation. By itself, the term ‘interdependence’ masks entrenched and systemic inequality.

COVID-19, Vulnerability and Grief (COVID-19 blog no. 3)

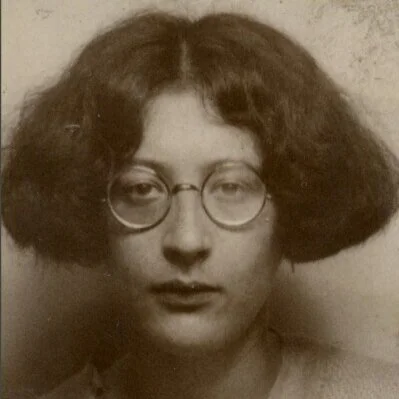

How to avoid getting distracted in Lockdown: Pursuing real hope with Simone Weil (COVID-19 blog no. 2)

COVID-19, Distractions, and Hope (COVID-19 blog no. 1)

COVID-19 Blog Project: Introduction

Brexit and Christian Identity: A Challenge for Political Theology

The turmoil in UK politics continues. Our country is split down the middle over Brexit, and the ongoing controversy is eroding many people’s faith in democracy and destabilising our current political order. Since the 2016 EU referendum two thirds of all voters say our democratic politics is ‘broken’ and a third of the voters in the 2019 European Parliament elections supported the Brexit Party, which gained seats from the other main political Parties.

Nigel Farage has explicitly included “traditional Christian values” in his future vision for Britain, and other supporters of a ‘clean break’ Brexit have similarly integrated Christian values into their political message. Leaders of Britain First have quoted the Lord’s Prayer as if it were a battle cry. Michael Gove has talked of the spirit of Protestantism as the inspiration for Britain to go it alone and leave the EU. And the far-right campaigner Tommy Robinson (real name Steven Yaxley-Lennon) has appealed to ‘British traditional Christian cultural identity’ to justify anti-Muslim prejudice.

As Christians we should be aware of the cost of promoting these particular interpretations of our religious values. The use of our collective Christian identity to justify a nationalist agenda, with its mixture of economic neo liberalism and social conservatism, is empirically contestable and ethically dubious. It also has worrying implications for a coherent and principled political theology.

The facts about Christian identity.

British Christian identity is neither monochrome or monolithic. There is no set of ‘Christian values’ to which all or most of us assent, but rather a plurality of attitudes. The changes in the lives of Christians over the last few decades have been demonstrated in the results of the annual British Social Attitudes Survey and by the work of contemporary sociologists of religion. This provides a complex picture of Christians in Britain, what we see as our core values, and our views of the place of faith in the public realm. What is clear is that the changes that have happened are a result of an interaction with demographic and cultural changes in British society over the past few decades.

Women are in the workplace in Britain in double the numbers of the previous generations which fundamentally changes the dynamics of home life for many. Relatives are attending the marriages of gay sons and lesbian nieces, looking after the children of bisexual friends and neighbours and learning about trans and non-binary gender identities.

Carers are looking after relatives and friends at home despite less and less practical and financial support from the state. Many people live far away from relatives and from the places where they were born and brought up and are unable to access longstanding networks of family or neighbours.

A new identity that goes beyond borders is also being forged. More of us work for firms in sectors dominated by multinational companies and where trans-national financial ventures are the norm. In many faith communities immigrants are the cornerstone of church life, and despite the rise in hate rhetoric and violence there is evidence of an overall ‘softening’ of attitudes to immigration in Britain as a whole.

Faith, and its relationship to identity, is becoming more diffuse. Studies including those by Linda Woodhead show that the attitudes on ‘personal morality’ of Christian churchgoers are the same as that of the non- churchgoing population (with two standout exceptions, that of the older generation, and those in conservative evangelical communities). The attitudes to issues of social morality such as poverty and immigration, are actually more progressive amongst faith groups than the general population.

Stephen Bullivant has shown the fact that the vast majority of ‘cultural Catholics’ do not have any contact with Church life, and may define themselves as having no faith identity, and this is having an effect on current religious practises.

Christianity, belonging and communal values

The assertion that promoting social solidarity in our ‘broken Britain’ is dependent on a particular understanding of traditional Christian values is not just questionable because of the facts of demography and cultural change for individuals that have been described above. It is also contestable if we take account of the changes in our communities and their relationship to the social and political order. This is manifest in the experiences of groups on the margins, or with multiple identities.

Our experience of community life is changing and this affects those Christians who participate in social action. Traditional and acknowledged structures of civil society and their place in our national political life have been much reduced. There has been a transformation in the patterns of voluntary activity and the relationship of faith-based and other third sector organisations to the political order.

The effects of neo liberal economic policies on our working lives, and consequentially on home life and our lives in our communities, cannot be underestimated. People are often working longer hours often for less money. Many are in insecure employment or barely getting enough guaranteed work hours, and hence income, to provide for a decent home life. We have endured, since 2010, the largest cuts to public funding, locally, regionally and nationally since 1930s.

Local authorities have had their grants from national Government cut by up to 60% (mainly in poorer areas) and the national average spending on public services is down 26%. Current state social provision cannot support the frailest and most vulnerable in our society. Further cuts and the introduction of Universal Credit on top of years of cruel benefit sanctions regime undermines any realistic conception of ‘social security’.

The Transparency of Lobbying Act 2014, commonly known as the Gagging Act, means less opportunity for the voluntary sector to input into national political debate. With local authorities unable to support services in the community, underfunded and besieged as they are, charities and other third sector organisations are bowing to a corporate agenda, often out of financial necessity.

The view from the margins is telling. Groups of people who are not in the majority culture may not easily fit with established understandings of British Christian belonging. Though sharing similar signifiers with other Christians, newly established immigrant communities have their own cultural experience of belonging, often both as members of an ethnic minority and as immigrants. And the experience of second-generation black immigrants of persisting racism despite their British citizenship is corrosive of social cohesion.

Further, those who have mixed identities, especially those at the ‘cutting edge’ may well have a very different experience of belonging. This can often be negative. Members of faith communities who transgress the boundaries of acceptable behaviour, particularly women or those with LGBT+ identities face a hard choice – stay in and conform or risk being excluded.

The political theology of Christian identity and belonging

We are faced with contemporary and urgent challenges within our faith communities on key issues of social change, on matters of family and gender relations, gender identity and sexuality and of economic and social justice. We need discernment to recognise new ways, and to question what old ways keep us from reading the signs of the times.

The theologian Edward Schillebeeckx maintained that the history of human beings, indeed the social life of human beings, is the place where the cause of salvation or disaster is decided. He asserted that salvation from God comes about first of all in the secular reality of history and not primarily in the consciousness of believers who are aware of it. A healing historical praxis is how the nature of God is confirmed.

“Holiness” Schillebeeckx says, “is always contextual: it does not take place in a social vacuum.” As Christians we are called to give concrete social and political commitments and it is through this that the field of ‘political holiness’ is opened up to us. Our love of humanity, that is our disinterested commitment for our fellow human beings, is a hallmark of the truth of our love of God.

Human experiences of injustice and innocent suffering and meaninglessness were, for Schillebeeckx, of a priori revelatory significance. Our immediate future challenges of injustice and innocent suffering are focused on economic inequality, climate change and mass immigration; all matters that need global solutions. The ethical action we are called to today cannot be limited to the nation state in our increasingly interconnected world.

Contemporary experiences of meaninglessness are often focused on matters of identity and belonging. But in political debates on these issues we are usually offered a binary model; either free market individualism or conservative communitarianism. False oppositions are made between personal freedom and community commitment, between individual autonomy and a more equal social order, between rights and mutual obligations.

We have to get beyond a binary model of either personal self- expression or the rich interdependence of the relational. Our individual human need for belonging and identity can only be met through community involvement, but allowing space for freely chosen interdependencies is how we can remake our communities anew.

Schillebeeckx’s ecclesiological model went beyond liberal pluralism whilst accepting in practice the opportunities of operating within it. He described the church’s role as an ‘action in solidarity’ over the threats to our humanity. This is a vision which is still faithful to the fundamentals of Christian doctrine but has a political dimension.

The post Brexit narrative: concealment or exposure

In the post Brexit political world there is a danger that the language of our faith tradition could be co-opted for an agenda more closed than open. As well as the appeal to ‘traditional Christian cultural identity’ from political activists on the Brexiteer right, some significant forces on the left have embraced national-populism to argue a red-brown case against liberal globalisation. These include several who have argued for a stronger role for faith communities in our national life.

The Blue Labour co-founder Maurice Glassman is a supporter of ‘The Full Brexit’ group and other key Blue Labour thinkers including Jonathan Rutherford have argued for the importance of national sovereignty to restore people’s faith in politics. Jon Cruddas joined other Labour MPs, including Lisa Nandy, in calling for Jeremy Corbyn to reject a second referendum and back a Brexit deal. They argue that this strategy is necessary to meet the appeal of the far right in Labour heartlands.

But does this an accommodation to a post Brexit narrative hide more than it reveals? Indeed, support for Brexit from those on the left appears contradictory for there was a clear right-wing ideology underlying the Leave campaign. Nigel Farage and the Brexiteer wing of the Conservative Party wish to turbo charge the free market neo liberal economics of the UK. This is the very ‘market fundamentalism’ that has riven the social fabric of our communities, and been rightly criticised by Christians on the left.

It is over a decade since the Financial crash yet the income of the majority of UK population has not returned to pre- 2008 levels. There is greater discontent with the economic order and its ability to deliver, and a greater understanding of the range and effects of poverty and inequality on sections of our society.

Brexiteers may appear as political disruptors but their aim is to override this economic discontent and achieve a new level of political consensus that entrenches the market fundamentalist status quo at a time when it is being questioned. In this context national-populism can be seen as a useful distraction, and accommodation to it a political mistake.

Nationalist-populism of the right and the left uses certain nostalgic cultural values, including a reactionary interpretation of Christian identity and values, and is counterposed to the socially progressive changes of the last few decades on women’s, black, LGBT+ and disabled people’s rights. This has the function of opening up a cultural front which gives cover for the further development of economic neo liberalism, precisely because it is not ‘liberal’. Christian thinkers, including those who consider themselves ‘post liberal’ or ‘post secular’, should worry about the way ‘Christian identity’ and ‘Christian values’ are used in this discourse.

We as Christians are presented with a choice. We can promote faith communities that are exclusive, based on a static conception of tradition, that co-exist with an increasingly socially illiberal political agenda. Or we can value internal diversity within our communities and remain open to the demographic and cultural changes in the contemporary experiences of the faithful. We have an opportunity for witness at this challenging political time.

Dr Maria Exall is a Research Fellow in Catholic Social Thought and Practice with the Centre for Catholic Social Thought and Practice and the Centre for Catholic Studies at Durham University. She has a PhD in Philosophical Theology from King’s College London. Maria is a national trade union representative and political activist.

Articles and links

www.natcen.ac.uk/our-research/research/british-social-attitudes

Institute for Fiscal Studies, ‘A Time of Revolution’ British Local Government Finance in the 2010’s www.ifs.org.uk

Linda Woodhead, ‘The Rise of “No Religion” Towards an Explanation’ Sociology of Religion 2017 78:3

Stephen Bullivant, ‘Europe’s Young Adults And Religion’: www.stmarys.ac.uk/centre/benedict-xvi/europes-young-adults-and-religion.aspx

Edward Schillebeeckx, ‘Jesus in Our Western Culture’ SCM Press 1987

Jonathan Rutherford ‘Why sovereignty matters for national unity: a warning’ at www.briefingsforbrexit.com 10/12/18

www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk/uk-politics-48694223 Labour MPs urge Corbyn not to go ‘Full Remain’ 19/06/19

Caritas Conference 2017: Mission in an Age of Austerity

Brexit, Workers' Rights and the Common Good

Working for a Better Future: What demands does Catholic Social Teaching make on government, employers and employees?

St Hilda Chair in Catholic Social Thought and Practice

Brexit Blog #9: Thinking about Brexit after Article 50

What’s love got to do with it?

In a recent judgment the UK Supreme Court upheld a law requiring that a UK citizen earn a minimum level of income in order to bring their non-UK/EU partner to live with them in the UK. The court accepted that this led to “significant hardship” which impinged upon their human right to family life. However, this was held to be justifiable on the grounds of the state’s “interest in ensuring that the couple do not have recourse to welfare benefits and have sufficient resources to be able to play a full part in British life."