The failed saviour

Counter-narratives in grassroots movements

This disruption of our daily monotonous routine illuminates what constitutes normalcy and unmasks the power structures that frame the function of everyday life. These powers of exception reveal us to ourselves rather than simply innovate. As a consequence, we are confronted with understanding citizenship from a different perspective in recognizing this power.

Domestic violence: A double pandemic?

The coronavirus is a public health crisis with serious global social implications. Like all emergencies, the virus has not affected everyone in the same manner. The UK government implored its citizens to ‘stay home’ in order to slow the spread of the disease. As a population, we withdrew from the public realm with the intent to save lives and protect our NHS; our homes were marked as places of relative safety. However, for many this was not the case. The restrictions imposed had different repercussions for many and the reality of living under lockdown meant that new dangers were able to flourish.

A spectrum of meanings: Who owns the colours of the rainbow?

Houses adorned with rainbows have become a common sight during lockdown. Usually in the form of children’s drawings stuck in windows, the rainbow has become a symbol of support for the NHS. From streets in Bradford to 10 Downing Street, from school playgrounds to Kensington Palace, the symbol of the rainbow in support of the NHS appears to have been adopted at every level of the political.

Rooting the Cross in its soil: the danger of sanitising grassroots movements during COVID-19

COVID-19 and the politicisation of data

Racial inequality and COVID-19: Why things can’t go back to ‘normal’ after the coronavirus

One day we will wake up to the news that there are no new cases of COVID-19. The British Prime Minister will take to the podium outside Number 10; he will announce an end to the lingering threat of new lockdowns and lift social distancing measures. This is the day we imagine, somewhere in our future, when life will seemingly go back to normal. But will we be happy with normal?

Dark times and the principle of hope: introduction

Shade and darkness - the evening of the deluge, by William Turner

A group of our final year Durham Theology and Religion undergraduates have been meeting weekly by Zoom during the long months of lockdown to reflect together on unfolding events. Speaking to others beyond our own ‘households’ has provided a helpful counter-point, air-pocket and sense of continuity for us all (I do not exempt myself from this – it has been a highlight of each week for me!) Towards the end of our meetings we decided to try to write up some of the strands of conversation as blog posts. The resulting blogs are collected here.

It is not an easy time to think or write, and the breadth of reflection here, honest and personal, drawing from our year long course in political theology but also ranging more widely, gives me hope. As the world we have been inhabiting has seemed both to shrink and yet also to become more truly – and at times horrifyingly – global, these pieces try to grapple with what all of this might tell us, and what kind of task might lie ahead. We wanted to write and share these as part of a spirit of meaning-making, of resistance to the fragmenting and isolating effects of the virus and its surrounding politics. Our conversations have not been private, but we have wanted to reclaim the public nature of academic reflection, and to speak and write as we have felt able at this time.

The themes of the blogs flow from a common sense that there is no ‘return to normal’ option available or desirable. But imagining beyond this very testing situation is not always easy.

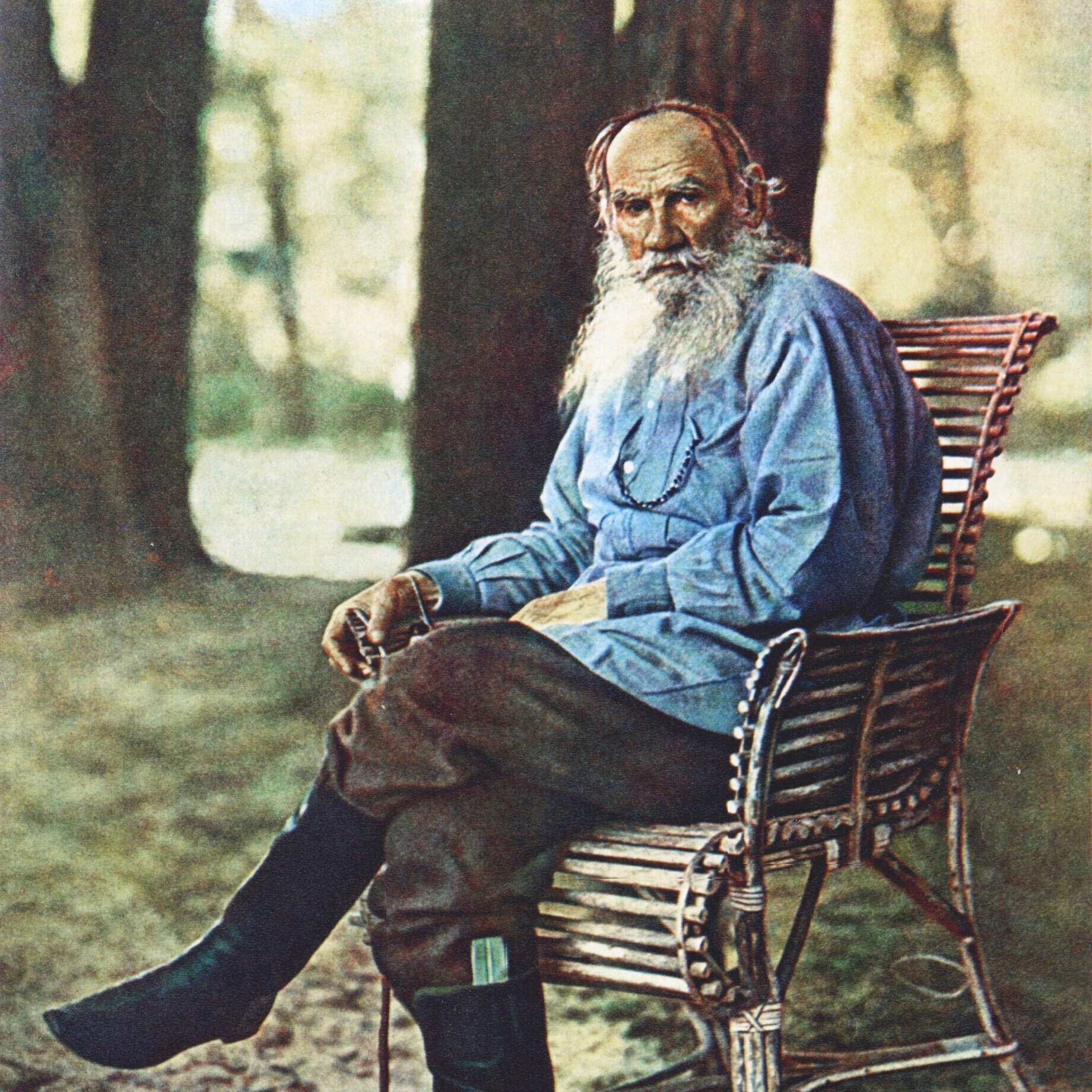

Didier Muller writes of Tolstoy’s insight that our imaginations can shrink in the face of such challenge, and this needs to be overcome; we desperately need new social visions at a society-wide level. Other blogs are more diagnostic of the fault-lines and pathologies of the politics of this virus: the battle over ‘data’, the radical inequalities exposed and exploited, and the sanitising and co-option of grassroots responses by government. Barbara Pressendo writes about the Bolsanaro regime in Brazil and the radical inequalities exposed in death rates there. Florence O’Taylor, a PhD student who has joined our group, writes on the history of mutual aid groups and the importance of their radical past and future. Emma Wilkinson, about to become an ordinand in the Church of England, writes about the use of the symbol of the rainbow and its long history of association with themes of hope, renewal, and unity. She concludes that its migration as a political symbol suggests both its power and that it evades any final or narrow belonging to a single cause. Olivia Barnard writes of one of the pandemics within the pandemic: domestic violence. Drawing on Hannah Arendt, she writes thought-provokingly on the role social media and the beauty industry has played in keeping open public spaces for those in unsafe households, and the changing nature of what solidarity might mean in this light. Rachel Bedek, a Canadian student, draws on German thinker, Carl Schmitt, writing of the need to pay diagnostic attention to the conflicting narratives of human worth and good citizenship at play in a “state of exception” (Schmitt’s phrase), emerging in tensions between state actors and citizen actors. Sarah Cotes draws on William Cavanaugh’s work on the myth of the modern state as our saviour to argue that the state has failed to ‘save’, and that we need to look elsewhere for a more stable form of hope. George Batchelor draws on the work of mid-century French political thinker and mystic, Simone Weil to argue that the pandemic has further uprooted an already uprooted way of life, and explores Weil’s notion of affliction: a form of suffering that can be difficult to find language and speech to process. Only love and justice are the practices that make such suffering finally able to speak in its own right.

The principle of hope here has been speaking together, trying to make sense of things, and daring to imagine that we are capable of a fittingly human response to these events.

Dr Anna Rowlands is St Hilda Associate Professor of Catholic Social Thought and Practice at Durham University, where she teaches a third year module in Political Theology.