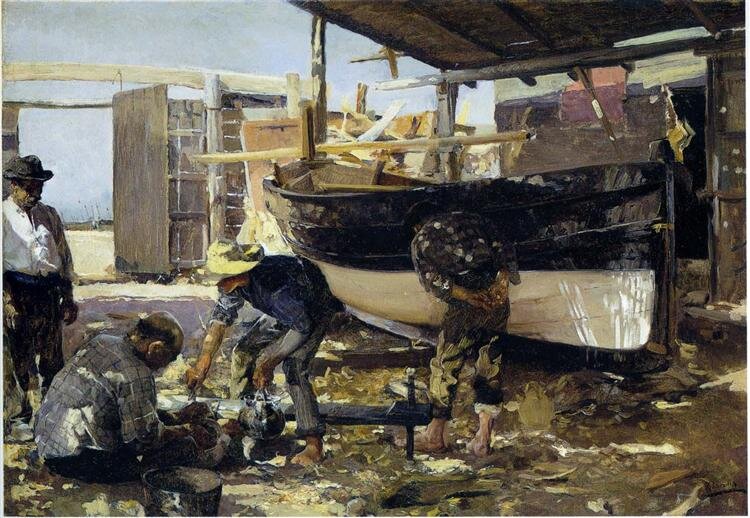

Boat Builders, by Joaquín Sorolla

Not needing to spend half my life travelling to and from meetings over the last four months of lockdown has had some personal advantages. I’ve attended more online seminars in the last 100 days than I have in a lifetime. I have read lots, getting up early, and spending a couple of hours most mornings ploughing through some weighty tomes. I have not always thought particularly clearly – I do my best thinking in the company of others, especially those whose lives are lived out at the margins and in the struggle for dignity – but long runs most days have, to some extent, given an alternative space for reflection and contemplation.

In one of the online events I attended early on, we heard from the North American Christian activist Shane Claiborne, someone whose commitment to peace-making and community-building I have long admired. One of the things I scribbled down in my notebook was his reflection that, as human beings, we don’t lack compassion but proximity. He attributed the thought to someone else but as I didn’t write it down, I couldn’t subsequently remember.

The idea, however, did get under my skin and became something of a lens through which to view this catastrophe. I was aware of concern and compassion everywhere, but in some places there appeared no outlet for it – certainly no physical outlet other than a boisterous Thursday evening clap for the NHS and Care Workers – whilst in other places the need felt overwhelming. Forced to stay apart at a household level, lockdown has exposed our divisions as a neighbourhood and as a society. People wanted to help but there were few outlets to do so. The vast numbers of people who signed up to volunteer with the NHS but have remained underused (or unused) is illustrative of the wider point.

A few weeks later, reading Wounded Shepherd, Austin Ivereigh’s most recent biography of Pope Francis, I remembered the source: “You recognise the Kingdom of God, Francis likes to say, not only because the hungry are fed but also because they sit at the same table as everyone else”.[1]

Proximity is a core thread running through the teaching and lifestyle of Pope Francis. As he put it in his meeting with migrants during his 2019 visit to Morocco:

…. the progress of our peoples cannot be measured by technological or economic advances alone. It depends above all on our openness to being touched and moved by those who knock at our door. Their faces shatter and debunk all those false idols that can take over and enslave our lives; idols that promise an illusory and momentary happiness blind to the lives and sufferings of others.

COVID-19 has exposed the ‘false idols’ within our society. This is a virus which has proportionately hit the economically poorest, BAME communities, and the elderly the hardest, both in terms of hospital admissions and of deaths.

Lockdown has been very different if you live in a large house with its own garden or in a high-rise tower block. Home schooling looks and feels very different if you have highspeed broadband and guardians who are university educated by comparison to those without access to the internet or whose parents were failed by the education system. Or whose first language is not English. The consequences of the necessary measures to stem the spread of the virus are likely not just to deepen poverty in the short term but also to deepen inequalities in the long term.

In the UK there appears to be some level of consensus, at least at the level of rhetoric, that things cannot go back to how they were before. These last four months could turn out to be our ‘teachable moment’ when we have come to the realisation that things cannot continue along the same trajectory. The number of people talking about the need to ‘Build Back Better’ is encouraging. However, that will require a need to ‘build back with’ rather than continuing to ‘build back for’. It will, in other words, require us to be close to (in proximity to) people who are not like us, rather than to simply have compassion for from a distance. This is challenging, painstaking, and, in my experience, gloriously enlivening work.

Angus Ritchie, Director of the Centre for Theology and Community in London, and a keen advocate for broad-based Community Organising, seeks to articulate a pattern of “inclusive populism”, which avoids the exclusionary versions of both left and right, and highlights the value of people working together on what they can agree on whilst learning to articulate more clearly that which currently divides them. He writes: “The solidarity and trust that are built by action on common concerns create an environment in which the more difficult conversations are much more likely to have fruitful outcomes”.[2]

The sort of inclusive populism Ritchie advocates takes us beyond what he identifies as the pretend and dangerous neutrality of secular liberalism into an understanding where we find commonality in the midst of difference by working together on what does and can unite us. George MacLeod, founder of the Iona Community, would have made a similar point: “Community is created by an exacting common task.”

In another important aspect, Ritchie’s space is not neutral, seeking to find commonality in a bridge space between rich and poor, black and white. It is rather a situated knowledge/wisdom and commitment that deliberately locates itself alongside those at the edge.

This need to enable and build these “proximity communities” is one of the great tasks of our time. Fundamentally, this is about relationships.

Martin Johnstone is a Church of Scotland minister who now works alongside a range of different groups and organisations working for justice in the UK and globally. You can find out more at www.attheedge.co.uk or follow him on twitter at @MartinAtTheEdge.

[1] Austin Ivereigh, Wounded shepherd: Pope Francis and his struggle to convert the Catholic Church (New York: Henry Holt & Company, 2019), p. 157.

[2] Angus Ritchie, Inclusive Populism: Creating citizens in the global age (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2019), p. 25.