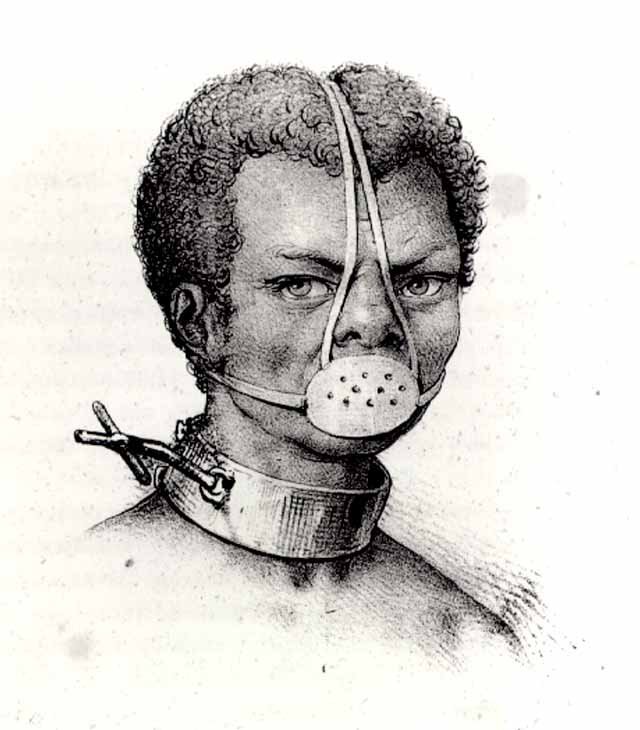

Portrait of Brazillian folk saint, Escrava Anastasia, by Jacques Arago

In this blog project, we have included a number of pieces focusing on the death of George Floyd, and this startling moment in the pursuit of racial justice. The main purpose of this blog project is to show the complexity of the issues thrown up around the pandemic, and this involves recognising the various intersections of race, gender, class, etc. as they play out in this context. However, what is notable about a number of these pieces is that although they talk about events happening during the pandemic, they barely talk about the pandemic itself at all.

To put it differently, in many ways, and although they talk about issues that certainly impinge on our lives in the pandemic, these pieces speak to issues that they present almost as external to it. As a curator, including them is perhaps an odd decision – intuitively, my aim is to create a series which holds together with something like cohesiveness or unity. Yet these ‘external’ pieces disrupt this unity.

There is a simple reason for this inclusion: the death of George Floyd, the Black Lives Matter movement, and the iconic scene of Edward Colston toppling into the river in a satisfying parallel to the slaves thrown overboard from his ships to drown in the Atlantic, is that they are pressing. They have their own force, which compels us to talk about them. We social, political animals cannot help but be swept up by these events, and to have our thoughts and words shaped to resonate with the themes of the time. And it feels entirely natural and fitting for them to compel us in this way – which is to say, including pieces which speak about them and not COVID-19 nevertheless just seems right.

In this, they also reveal something about the preconceived notions of unity and cohesiveness according to which they would otherwise be excluded: that these are unnatural, unfitting, and uncompelling. That is, they reveal the necessity to reject the neat totality of ‘subject matter’, and for me as curator to abandon my expectations about the shape of my own project. And I cannot help but think that there is something prophetic here.

Until I received these articles, I viewed curating this blog as a process characterised by three movements of unification: first, the construction of a unity by placing the various pieces together within a coherent ‘collection’. Second, I aimed for this unity to (at least approximately) to represent or correspond to the unity of the pandemic as a phenomenon, which presupposed the grasping of that object as a unity by my thought. Finally, insofar as this collection also seeks to be a point of access to the object by preserving insights and experiences of the pandemic for future reflection, I was aware of my imposing the unity of the collection on the phenomenon of the pandemic itself, which will be viewed through the keyhole of these curated boundaries.

However, Francis enjoins us to a different view. In Evangelii Gaudium, he writes that our fulfilment lies beyond the “horizon” of the future, and that we must therefore refuse a logic of “space” which seeks to possess totality in the present, instead facing up to its “limitation”.[1] Gaudete et exsultate explores this theology of time in the context of knowledge. Here, Francis warns against an attitude in which we deceive ourselves into thinking that we have “an answer for every question”.[2] He associates this attitude with a “Gnosticism” that attributes an inflated power to the intellect over and against God’s transcendence in an attempt to close down the possibility for God to surprise us by acting in ways we cannot anticipate.[3] We might say that Gnosticism’s pretension to total knowledge refuses to recognise the limitation of the present, instead pretending to see beyond the horizon of the future and therein anticipate the surprises which it may hold. Finally, this is reflected in the call of Laudato si’ to recognise that “everything is connected”.[4] One of the ways this connection bears out is in a mystical communion of interrelation between everything in creation. This manifests in a complexity which defies total expression by any one particular knowledge or discipline; an insight which undergirds Francis’ call for an integral ecology that looks to a “broader vision of reality”,[5] rather than treating ecology as one self-contained knowledge among other self-contained knowledges. Hence Laudato si’ “does not pretend to know it all” in its approach to the world,[6] instead looking to other disciplines for its understanding of the environmental crisis, as well as championing a stance towards creation which Katherine Keller describes as a “mystical unknowing”.[7]

In short, Francis enjoins us to a view of history that requires epistemic humility towards the world within it. I, as a single knower, cannot hope to possess total knowledge, because there is always something about the world that lies beyond my view. There is always the possibility for a surprise that is un-anticipable precisely because it comes out of ‘nowhere’; that which ‘is not’ yet here, but lies beyond the edges of the current moment, across the horizon of the future.

This refusal of totality requires us to think about the objects of our knowledge in a different way. It disrupts our claims to possessing the unity of the phenomenon we seek to know (the second unity), which in my case means the unity of ‘the pandemic’, because it may always exceed our anticipations. In turn, this casts doubt on our ability to faithfully reproduce this unity, for example in a cohesive blog series (the first unity): it is difficult to copy something one has not (or is uncertain that one has) fully seen. Finally, this means that we need a healthy skepticism of our ability to access a phenomenon through the unities we construct, for example by getting a complete picture of the pandemic through this blog series (i.e. to perceive accurately under the third unity).

In other words, Francis teaches us that we may not know ‘the pandemic’ yet. Perhaps some factor will emerge from the future to radically reconfigure its boundaries, and thus the conditions for our adequately conceiving of it. The subtle insight of these pieces is that the force with which the issues of racial justice impose themselves upon us today may thus be indicative of this future form; a future unity which appears as incoherence in the present only because its consummation lies in the negativity beyond the horizon of the future. Hazy boundaries enable us to be sensitive to this possibility; to discern the surprising, rather than foreclosing it with predetermined notions of what this unity ‘should’ be.

More generally, read in this way, it becomes clear how the uncertainties and ambiguities of editorial decision-making are a snapshot of life in history. Time outstrips us, as does the history that unfolds in its passing. To live in history is to live with uncertainty; something that is all the clearer in moments of heightened historical awareness, such as this one. We are living through The COVID-19 Pandemic; a moment pregnant with untold fearful possibilities. We are hurtling into the darkness, not just of an unknown future, but likely a dangerous and terrible one.

Yet if Francis teaches us to embrace uncertainty, he teaches us to do so in hope. In Evangelii Gaudium, the horizon of the future nevertheless opens out onto future fulfilment. Likewise, the indeterminacy which Gnosticism seeks to eradicate is that of divine transcendence, and its consequently unpredictable providence. Finally, Laudato si’ looks forward to a final consummation of all creation in a Eucharistic communion that puts to rights the relationships within it in all their breath-taking complexity.[8]

It is easy to think that hope is opposed to uncertainty. Viewed in this way, Francis’ call for hope seems even foolish in the context of the terrifying uncertainty of the present. But a hope without uncertainty is a hope that refuses the indeterminacy of the future; a Gnostic hope that cannot tolerate consolation in anything but its predetermined object. It is for this reason that I suspect these pieces’ refusal of totality may ultimately be prophetic: not just because it witnesses to the uncertainty of the situation, nor even because it is sensitive to the pressing nature of issues of racial justice in this moment, but because in doing so it witnesses to the Christian hope for which this indeterminacy is the condition.

Dr Nicolete Burbach is a consultant research associate in the CCSTP, and curator of the COVID-19 Blog Project

[1] §222-223.

[2] §41.

[3] §36.

[4] §91, 117.

[5] §132.

[6] Lorna Gold, ‘The Disruptive Power of Laduato Si’ – A ‘Dangerous Book’’, Laudato Si’: An Irish Response, Sean McDonach (ed.) (Dublin: Veritas Publications, 2017) pp. 91-104, p. 95.

[7] Catherine Keller, ‘Encycling: One Feminist Theological Response’, For Our Common Home: Process-Relational Responses to Laudato Si’’, Jonn B. Cobb Jr. and Ignaio Castuera (eds.) (Anoka, Minnesota: Process Century Press, 2015) pp. 175-186, p. 178.

[8] §236.